The Evariste Galois Bi-centenary Conference

Institut Henri Poincaré, Paris

October 24-28, 2011

Dr. Roy Lisker

Part 1; First Installment

A visit to the Institut de France

to examine the manuscripts of Evariste Galois

"At the same time his [the mathematician's] mind was gauging everything that was said in the course of conversation. He resembled the man walking in the garden who, with his sword, cut off the heads of all the flowers which stood higher than the rest. He was a martyr to his own exactitude, and was pained by anything that stood out, in the same way that people with delicate eyesight are pained by too strong a light. Nothing was indifferent to him, provided it was true. As a result his conversation was odd" .. "A newsmonger mentioned the bombardment of the fortress of Fontarabia, and he immediately gave us the properties of the trajectory described by the shells; he was delighted by this, and quite willing to remain in ignorance of the outcome. A man complained that the previous winter he had been ruined by floods. 'I am very pleased to hear that', said the mathematician, 'I see that I was not mistaken in my observations, and that there was at least two inches more rainfall than the year before.'" Montesquieu, The Persian Letters, 1721, translation by C.J. Betts

Institut de France

October 25, 2011 was the bicentenary of the birth of Evariste Galois . This report covers the highlights and episodes of the week-long commemorative conference , October 24-28, held at the Institut Henri Poincaré. It touches upon the 'mathematical content' of the conference only when it is relevant.

Evariste Galois is the mathematical prodigy who invented modern algebra in 1829 at the age of 17, then was killed in a duel on May 30th, 1832. The basis of the quarrel and even the name of his adversary are disputed to this day, but the duel was probably fought over political differences, with the suggestion of a failed love affair.

Bourg-la-Reine

Evariste Galois was born in Bourg-la-Reine, now a suburb of Paris, on October 24, 1811. His father, Nicolas Galois, was its' mayor, while his mother, Adelaide-Marie Demante, came from a family with political connections. On July 28, 1829, Galois' father, who was a "republican" (in the sense of "Vive la Republique!", perhaps a "liberal with republican sympathies", meaning that he would have acquiesced to a constitutional monarchy, but not to the return to the past glories of Louis Quatorze promoted by the reign of Charles X) committed suicide. It was only a few days before his son took his first examination to enter the Ecole Polytechnique. It is not surprising that he failed. The Ecole Polytechnique at that time was the only place where an aspiring research mathematician could get the education required for his career. Its dazzling research faculty would have been the pride of any university at any time

Nicolas Galois had been disgraced through a malicious practical joke played on him by the 'ultra-royalist' curé of Bourg-la-Reine. (The ultras were the partisans on the extreme right pushing for a full theocracy administerered by the Jesuits.) The priest had forged some insulting verses, attributed them to Nicolas, then sent them to members of the Galois and Demante families. A riot broke out during the funeral procession of Nicolas Galois' corpse to the cemetery, in the course of which the nose of the hostile priest was broken by a stone thrown at him from the crowd.The times were indeed ripe for revolution.

From the day of his father's suicide to his own death, 3 years later, Evariste Galois was a political firebrand, a leftist extremist not far from an outright Jacobin, someone who in today's France would be classified as an "enragé". Parenthetically, the fear of a "Jacobin" uprising, (a la Robespierre) sparked terror in the hearts of the returned aristocratic exiles and the clergy. Stendhal, in "The Red and the Black" relates how, in the seminaries of his fictional Besancon, the students received regular training in the use of firearms and the martial arts.

In anticipation of the conference at the Institut Poincaré, I read two excellent biographies of Evariste Galois: Tony Rothman's , which appears on the Internet, and the "official" biography by Pierre Dupuy, published by the Ecole Normale Superièure in 1896 . The biography by E.T. Bell that appears in "Men of Mathematics" is pornography, not history, and is not being consulted.

Reading these accounts I learned that a complete file of all of Galois' surviving research manuscripts is archived at the Institut de France, a venerable (and much ridiculed) organization for the preservation of "immortals", living or otherwise, in France's scientific, artistic and literary establishments.

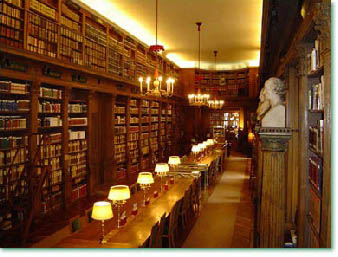

Library of the 5 scientific academies

The warren of buildings of the Institut de France hold a number of libraries. Those of the 5 scientific academies are grouped together in one building. One also finds there the Bibliothèque Mazarine, with special collections in Renaissance and Medieval manuscripts. This, I thought at first was the one containing the Galois archive.

The folio of pages that I wanted to consult is indexed MS2108. There are only 60 pages in the "fair copies" of Galois' research, but the folio also holds many fragments, drafts, some letters, and several articles that were copied by his amanuensis and friend, Auguste Chevalier.

Since this is France, I prepared myself for many formalities to be accomplished before I would be allowed to look at the Galois papers. I should explain that my experience of living in France goes back to the 1960's, and that many things have changed since then. My quest began at the library of the Institut Poincaré.

Institut Henri Poincaré

The Institut Poincare library occupies an entire floor of the building. This floor, by the way, does not have a number. The floor numbers in the side panel of the IHP elevator read "-1,0,2,3,4"! A strange algebraic object - algebroid, groupoid, clone, clan? - if there ever was one. 0 is of course the ground floor. In the English-speaking world this would be the first floor: it all depends on one's notions of proper beginnings. To get to the library, the staff enters the elevator with a special key that it inserts into a lock on this panel. The elevator halts on the library floor for them to step out. Visiting fellows who want to use the library must walk from the ground floor up to the next; admittedly not a very arduous task.

The library has a monastic climate and not too many visitors. The IHP is primarily a center for research, not for study, for conferences rather than courses, although it does offer both. There were two librarians in attendance when I entered the IHP library on the morning of October 17: a middle-aged woman (translation:younger than me), and a tall, gentle-mannered North African who's worked there for many years; I first met him in 1986. They explained that I would have to call up the Bibliothèque Mazarine (at the time we all imagined that the Galois archive was kept there) and make an appointment.

It turned out to be easier than I had imagined. A lilting voice floating across the wires advised me to come down with my passport and sign in at the reception counter. This seemed to me to be too good to be true, so I went back onto the Internet.

From the homepage of the Institut de France on the Internet, I learned:

- That there are several libraries at the Institut de France; Galois' manuscripts might be in any one of them.

- That, in order to use the libraries of the Institut de France I had to have recommendations from 2 members, (normally appointed for life).

- That the original manuscripts of Evariste Galois had been put together in a collection in 1906, but had since deteriorated so badly that they had to be copied on microfilm before discarding the originals.

The Bibliothèque Mazarine and the Institut de France are located in an 18th century sprawl of buildings beside the quais of the Seine, directly across from the Pont Neuf, the Pont des Arts and the Louvre. I quickly learned that crossing from the Pont des Arts to the Quai Conti was mortally dangerous; a car came charging at me like a humped dinosaur, followed by a commando driven motorcycle. The rudeness of Parisian street traffic was satirized by Montesquieu (in the Persian Letters) as early as 1721.

An immense courtyard, a parvis for stationing horses, is spread out like a silken meadow before the headquarters of the Institut de France. To the back of this horse lot, around the middle, one finds a gargantuan edifice, a reconstruction of someone's idea of a Greek temple, surmounted by a dome that combines suggestions of Brunelleschi with the tulip dome of an Orthodox church. Entrance to this mastodon is via a surprisingly modest doorway to the left.

There I encountered an elderly woman sitting behind a glass partition (translation, about my age) dressed in a grey business suit. She got right down to business: where was my passport? This, ( combined with the fact that, as she put it "You speak an excellent French") appeared to be sufficient credentials, so she directed me to a doorway that led into a courtyard. The Bibliothèque Mazarine, she explained, was on the first floor and could be reached by a staircase to the left.

I entered one of several doors to the left and asked the porter for the way to the Special Collection of science manuscripts. He, at last, gave me the correct information: the library I wanted to go to was actually on the 2nd floor of the Institut, and could easily be reached via an elevator down the hall to his right.

The instant I stepped out of the elevator onto an elaborate green tapestry embroidered with hundreds of fleur-de-lis , I realized that I'd entered the very heart of French civilization: the lounges, ballrooms, alcoves and meeting rooms of the fabled 5 academies of the Institut de France!

This floor held 3 rooms, connected length-wise: an antechamber with the Bibliothèque de I'Institut off to the right; a posh assembly room with tables and chairs for dining and lounging about; and a formal conference room. Not knowing at first where the library was, I turned right and walked across the lounge into the conference room.

It was somber if not entirely sober, motley with patches of illumination from chandeliers holding bright electric bulbs shielded by cylindrical glass cages. Down the long axis of the room flowed one of those very long, narrow dark-varnished loop-shaped wooden meeting tables that one sees in movies set in the ministries of planetary empires. On a ledge at the far end of the room stood a statue of Louis XIV (at least I think that's who it was), extending his greatness (if not exactly his benevolence) over all mankind. A row of computer monitors extended along the right wall. At the far end of this, at a comfortably imposing height, stood a movie screen.

A cleaning woman, an African immigrant, was fixing up the room following a meeting in which, no doubt, tariffs had been decided for trade between Mars and Jupiter. She indicated that the library was at the opposite end of the hall.

It was indeed; and the door was open. Inside I encountered two librarians, both young women, full of solicitude and eager to help. They explained that the library would not be open for the public until noon, a mere 8 minutes away. I was invited to wait in the antechamber outside until they were ready to receive me.

This antechamber was grandiose, just like everything else in the building. Most notable was a great tapestry hanging on the wall in back of the elegant staircase, which itself descended from a wide- grilled wrought-iron banister. The furnishings were all imitations of Louis this-and-that, the ceiling exceedingly high. Around the room stood glass cases holding books from the Special Collections of the library, with little printed cards describing their contents, age, authors, publishers, etc. The overall theme of the exhibition was "La Gastronomie dans les Collections de la Bibliothèque de l'Institut ".

Nor will I be remiss in my duty by neglecting to mention the plaster busts of half a dozen distinguished worthies from bygone days. Notably among them: Francois Joseph Bosio, (sculptor) 1768-1845; Auguste-Gaspard-Louis-Desnoyers (engraver) 1778-1857; Victor-Joseph Etienne De Jouy 1764-1846 (a bit of everything); Emanuel de Pastouret (lawyer) 1756-1840.

Sitting there quietly on a couch I had the impression that they were all winking at me, as if we were all engaged in some private conspiracy. At ten minutes after 12, the door to the library opened again and I was invited inside.

An earlier view of the Institut Library

The room into which I was admitted was considerably rectangular. Dark and inviting, its' ambiance was the epitome of a welcoming library reading room. The relatively narrow bottleneck at the entrance gave way to a tripartite division: alcoves to the left illuminated by light from the street; shelving, doors and a balcony to the right; and an elongate table covered with books and learning all the way from the entrance to the back of the room. Here stood half a dozen women, dressed in charming smocks like Marie-Antoinette's milkmaids, and one man, all consumed with curiosity and suspicion at the arrival of this ancient American. It was not an unfriendly suspicion, yet it seemed to ask: did I really belong there? In a few of the niches against the windows scholars were deposited, ostensibly engaged in research.

The librarian at the entrance instructed me to walk to the far end and speak to the persons there. Not being certain that I would be admitted, she allowed me to keep my backpack. When I arrived at the far end I was teamed up with a blond woman, whose sweater was red, and of age about 40. (Journalists, and writers in general, estimate the ages of the characters in their narratives by their notions of what makes a good story. In fact, anyone younger than myself could very well be in her 40's).

Acquiline nose, pumiced cheeks, russet hair, her look scornful, her manner sardonic. When I told her that I wanted to consult the Evariste Galois archive, (otherwise known as folio # 2108), she snorted:

"Did you write a letter in advance? Do you have a recommendation from someone at the Institut de France?" I admitted that I had neither; followed of course by the rehearsed ritual of explanations: I was a long-term fellow at the Institut Poincaré, registered for the Galois conference, purposed to write up a report, etc ..

She frowned, nodded, thought for a moment,then asked: "Is it just for this one time?"

Yes, absolutely, just for today.

A sunny disposition broke through all the stern symptoms of distrust;it had never been far away. Smiling broadly, she pointed to the reading table: "Why don't you go back to the front, leave your back-pack there, come back and take a seat here, at stall #40?" When I came back I was self-debarrassed (vintage Franglais!) of my passport, following which she handed me 3 forms to fill out.

My case was now taken in hand by a much younger woman in a blue smock, a veritable 17th century belle transposed to the 21st. I asked her about the microfilms for the Galois archive. In fact, I was told, all the documents were on paper. The librarian explained that the microfilms had deteriorated so badly that they also had to be disposed of. Before doing so, the library had photocopied every page and bound them all in a single volume. I sat down, filled out the 3 forms, and waited.

My personal attendant disappeared into the stacks and returned about 10 minutes later with an enormous book, one of those things with hard covers that look as if they're saturated with lichens and algae from a stagnant pond, about 20 inches high and a foot across.

So it was with the greatest delight that I spent the next 2 hours embroiled in the contents of dossier #2108. Quite apart from the mathematics, which I know quite well through the study of a variety of textbooks (from Dehn to Artin to Rotman to Herstein) and which hardly justified a special visit to the Institut de France, these pages overflow with revelations about the personality of Galois, his working methods, the advantages and handicaps of writing technologies in an age before typewriters and linotype machines, how pages were blotted, pens broken, ink smeared or spilled. They are a treasure trove, a rich mine of insights into the turbulent times in which he lived, his sorrows and joys, his way of doing mathematics.

There is something very remarkable is the exquisite care with which the fair copies of his mathematical papers were composed before being sent to the Académie des Sciences. How maddening it was to him to have to rewrite the same "Premier Memoir" 3 times because the Académie had lost the first 2 copies! One can offer several reasons for this:

(a) Mathematicians are normally distracted and absent-minded, they lose things all the time.

(b) The storm-clouds of the revolution of 1830 were already lowering, menacing and very dark by 1829. Once again Stendhal's novel, "The Red and the Black", reveals the suppressed violence that had accumulated under the repressions of the 2nd Restoration of Charles X.

(c) Of course, in a stuffy Académie filled with famous mathematicians (Cauchy, Fourier, Poisson, LaCroix, Libri) a high school student named "Evariste Galois" was "just a kid", someone unlikely to have discovered anything of real interest for mathematics. ("Just leave that package, sonny, on the desk in the corner over there. The cleaning lady will understand (perhaps) and won't throw them out.. ")

In fact, when Galois submitted the 3rd version in January of 1831, he was no longer a high school student when the memoir was submitted; he was a high school drop-out! He'd been expelled from the Ecole Normale Superièure (then called the Ecole Préparatoire) for publishing a nasty though essentially accurate letter condemning the behavior of the school's principal during the events of the revolution of July 1830.

Although Galois was a troubled youth living in troubled times, his 3rd version of the Premier Memoir, (with its 8 Propositions that lay the foundations for modern algebra), is a masterpiece of aesthetically skillful, lucid penmanship: the columns go straight down, with space left on the margins for additional comments and corrected versions of the propositions.

In marked contrast to these pages are the scribbled drafts on which he worked out his ideas: words emerge here and there under a deluge of crossings, blotting and erasures.

One sees him trying out pens that refuse to function properly. On one sheet he writes out his name a dozen times in a clear attempt to get the pen to move smoothly. There is the occasional satiric doodle;and random sheets covered with letters, numbers and equations

(Galois invented ( in Proposition 1, Scholium and marginal additions) the technique of working with collections of symbols, or 'indeterminates' in their own right, as in modern algebra).

Proposition 1

One finds pages turned in all 4 directions, with equations, letters and numbers spread across it and intersecting each other . It was most unlikely that the librarians would allow me to turn the massive folio around, either clockwise or counter-clockwise!

For this 3rd copy of his memoir, (which, at last was read by Poisson and LaCroix before being rejected) Galois wrote a long preface filled with bitter reflections. In the fashion of any angry young revolutionary, the bonfires of outrage stoked from recent painful experiences ,exacerbated by neglects and slights, Galois rails against the entire scientific establishment for ignoring and losing his work.

Much has been made of this story by novelists and biographers, good and bad, owing to the irresistible sex appeal of its central motif: the blindness and vanity of the older generation when confronted with the work of a young genius. The truth is, of course, far more nuanced. Although the famous, well established mathematician Auguste Cauchy, has been blamed by historians for losing the first version of the Premier Memoir, he actually urged that Galois be admitted to the Ecole Polytechnique without examination, and even recommended him for the prize in mathematics from the Académie des Sciences.

The twin claims of historical necessity and scientific progress are more often than not in conflict: Galois' memoir was lost because Cauchy, a reactionary royalist, an ultra, went into exile following the abdication of Charles X on August 4, 1830. Although he eventually returned to France, he did not recover his former position in the scientific community until 1849.

On February 12, 1830, Galois submitted the second version of his memoir to Joseph Fourier, today even more famous that Cauchy for the invention of the Fourier series, Fourier transform and the theory of heat. Fate once more intervened and Fourier died in May before he was able to read it. From Wikipedia:

"Fourier believed that keeping the body wrapped up in blankets was beneficial to the health. He died in 1830 when in this state he tripped and fell down the stairs at his home." A 3rd version was then written up and sent to Poisson. There is no way of making a comparison with the composition and distribution of texts at that time and the situation today. Since 1980, when I first began doing creative mathematics, if there is a result that I want others to know about I print up dozens of copies and pass them out at conferences. This is considered by many to be in the worst of taste, but it is a fact that by doing so in 1985 I engaged the attention of René Thom, who was instrumental in arranging for me to participate in the 11th General Relativity and Gravitation conference in Stockholm in 1986. It also lead to good and fruitful conversations. Of course I think like a journalist and, as we know, mathematicians despise journalists. (Ferment Magazine editorial: Disdain)

After his expulsion in December 1830 from the Ecole Normale, Galois concentrated on political activism. By May 9th, 1831 his passions had been inflamed to a peak of self-destructive fanaticism. One might even argue that he was deliberately throwing his life away.

May 9, 1831 was the date on which, at a republican gathering at the Vendanges de Bourgogne restaurant ( then in the rue St. Antoine, therefore close to the Bastille) Galois raised a toast to the new king, Louis-Phillipe, goblet in one hand and a knife in the other. He was arrested the next day, but acquitted at the trial. However he was intercepted again, that July 14th, (Bastille Day) marching across Paris wearing an outlawed military uniform, carrying a loaded rifle and (once again) knives.

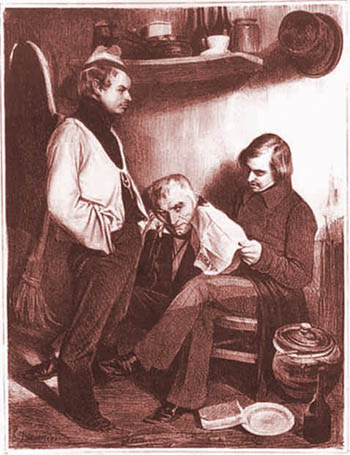

Prison Ste. Pelagie (by Daumier)

Under the circumstances it is surprising that he was sentenced to only 6 months in jail, commuted for reasons of health, his youth, and his acknowledged brilliance. His death was as much suicide as murder; if he hadn't been killed in a duel on May 30th, 1832, he might well have died in the republican uprising that erupted a few days after his funeral on June 2nd. In the June Rebellion 800 persons, mostly students, were massacred by the government.

It is high tragedy. In politics as in culture, the 19th century was the golden age of grand opera. It is a bitter, horrible story. But I find myself a bit irritated by people who dwell on the theme of the "great loss to mathematics" occasioned by the premature death of Galois. "Mathematics" is simply out there; one can neither add nor subtract from it. My favorite counter-example is the early death of Mozart, at age 34. On November 10th, 1972, Ludwig van Beethoven arrived in Vienna to study with Mozart. But Mozart had died a year earlier on December 5, 1791.

Imagine what a terrible "loss to music" it would have been, had Vienna been the scene of fierce competition between these two acknowledged giants! They would have stifled one another completely. The loss to "Music" would have been incalculable.Mozart had to die so that "music" (through Beethoven) could live!

And imagine that Galois had lived another 30 years and developed all of modern algebra. One of the consequences of this would have been that the introduction of the "new math" into secondary education might have happened a century earlier, thus ruining the interest and competence in mathematics for several generations of people of intelligence who didn't happen to be research mathematicians!

Or it may have gone the other way: all the sciences, notably physics which relies heavily upon mathematics, would have known accelerated growth, the atomic bomb would have been invented by 1870 and we'd all be dead by now!

Such speculations about the "loss to mathematics", or "loss to mankind", are foolish. (Continued at Galois2)